I can’t believe I am finally publishing a blog. I have started writing about at least 5 or 6 different subjects, but I often get distracted and move on to research something else, and forget to go back and finish what I was doing. ***SQUIRREL!!!***

Oftentimes**, when a user swipes up on the screen while using an application in an iOS device, or presses the home button (on those devices that still have one), or if they receive a call while using an application, the active application is sent to the background. A “snapshot” of the current screen is taken in order to provide a smooth visual transition while changing screens.

** Developers can choose to disable this, to use an overlay image, or to hide certain fields, for security reasons, for example.

From iOS 10 on, these snapshots have been stored as KTX files. KTX is a Khronos Group compression format that provides a container for multiples textures or images. This format usually requires less memory and is faster and more efficient than other types, presenting an advantage for mobile devices. A more detailed review of the KTX format is beyond the scope of this post, but the specs can be found on the Khronos Group website.

These snapshots can be located at:

/private/var/mobile/Library/Caches/Snapshots/<bundleID>/<bundleID>/

/private/var/mobile/Containers/Data/Application/<ApplicationUUID>/Library/Caches/Snapshots/<bundleID>

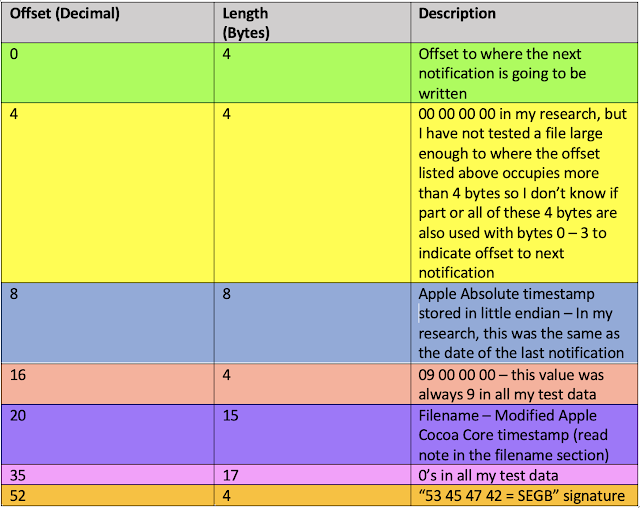

Through research I found that the relationship information for these snapshots was stored in the applicationState.db, located in /private/var/mobile/Library/FrontBoard… but of course, it wasn’t stored in a simple way… it was stored in a blob within the database – you guessed it! In a binary plist within a binary plist.

I could go manually parsing the snapshots information for each of these applications one by one, but I would probably fall asleep halfway through the second one. I needed to find a way to automate this process, so I talked to my good friend and mentor Alexis Brignoni (@AlexisBrignoni), since he is very familiar with bplist inception, Python, and mobile devices in general. Our solution?

Methodology

I have always said that the best way of forensically examining a Mac is by using a Mac. I think this also extends to iOS devices. There are several tools out there that do a fantastic job of parsing iOS extractions, but what do we do when the tool does not support a specific artifact? Or even when the tool does support it, it is our responsibility to understand where the reported values come from, and to make sure they are correct, especially if someone’s freedom depends on it.

So far, my favorite way of viewing KTX files has been to “Quick Look” them with Finder (while being a responsible forensic examiner and making sure they are write protected so I don’t step all over the evidence).

Brigs wrote a Python script (SnapshotImageFinder.py) that would extract all the KTX snapshots from the iOS extraction. I then created an Automator Quick Action that converts KTX files to PNG for usability purposes. Finally, Brigs created SnapshotTriage.py. This script first identifies and extracts the incepted bplists related to our snapshots from within the ApplicationState.db. Then, it makes an HTML report for every application that contains snapshots in our iOS device. This is just a quick summary of the methodology we used - for a detailed explanation please check out Brigs’s blogpost.

By the way, iOS Snapshots remind me of Recent Tasks in Android – If you don’t know what I am talking about, here is a great post by Brigs, you might be missing out on great evidence for your cases.

Forensic Implications/Case Scenario

Imagine a case where our suspect (John Doe, of course) has recorded a video of himself committing a crime using the native Camera app of his shiny brand new iPhone. In the middle of it, Mr. Doe suspends the application (maybe he received a phone call while he was recording or maybe he got paranoid and decided to get rid of the evidence). Of course, the suspect knows his way around technology and also emptied his “Deleted photos” folder within the native iOS app. We know iOS devices are not too forgiving with deleted data.

While examining the full file system extraction of Mr. Doe’s phone, we recover several KTX snapshots from different applications. These snapshots, along with other awesome files such as KnowledgeC, plists, etc. can help us paint a better picture of what was being done on the phone around the time of the crime.

In particular, we recover the following snapshot from /private/var/mobile/Library/Caches/Snapshots/com.apple.camera/com.apple.camera

While this video may no longer be there, it might prompt us to further investigate… The timestamp associated with the KTX file might give us some perspective. Or maybe it could provide additional clues for our investigation. Maybe he shared this video with someone, uploaded it into social media, or moved it into a secret app. Maybe we could serve a search warrant to Apple for iCloud backups. Maybe, just maybe, we might get lucky and find a video approximately 21 seconds long, recorded around the time indicated in the timestamp.

“Every contact leaves a trace.”- Professor Edmond Locard

Even though Locard’s Exchange Principle is often applied to tangible evidence such as DNA or blood splatters, it very much applies to digital evidence as well.

It is extremely important that we train our forensic personnel or first responders to limit their interactions with digital evidence to the minimum necessary to preserve it. You don’t want to be explaining to the jury why these snapshots have timestamps dated after the police was on scene, or even worse (in my opinion), have a murderer walk away free because we destroyed a key piece of evidence for not being careful.

Note: Our research has been primarily focused on iOS 11 and 12, but we are planning on expanding it to include other versions. We are also currently doing additional research on the timestamps located within the bplists. As always, please validate, validate, validate! Also please feel free to chime in if you have any additional info, because this is how we grow as a forensic community.

Have you tried `sips -s format png input.ktx --out output.png` for conversion?

ReplyDelete